Breathing Lessons: Southern Arundel Residents Struggle to Fight Pollution

56-year-old loophole stifles community voices in fight over gravel mine

By: Lilly Howard

Tracy Garrett moved to Sands Road in Lothian in 1967, the same year Anne Arundel County granted Westport Reclamation a renewed special exception permit, which is grandfathered under 1957 environmental laws. That piece of paper doesn’t have a condition authorizing county access, so county enforcement agents can’t step foot on site without permission from the owner without risking a claim of trespassing, according to Anne Arundel County.

Since Garrett moved to the area, at age 8, more industrial facilities have become her neighbors. And they’re not what she and other residents consider positive additions. Residents of Lothian have complained for decades about excessive truck traffic, noise and air pollution. Westport is a sand and gravel mining operation as well as a reclamation facility, meaning it reclaims construction materials at sites and is permitted to do rock crushing operations that cause excessive dust.

In 2015 Garrett and fellow Sands Road resident Celestine Brown collaborated with the University of Maryland School of Public Health and Patuxent Riverkeeper, Fred Tutman, to analyze the health impacts in the Lothian area. There are 33 industrial sites, 22 of which are in operation, within five miles of each other, according to the report. The assessment also found two landfills with histories of accepting cancer-causing materials.

“You don’t have to be a scientist or environmentalist to know this is impacting one’s health. You just have to go outside,” said Garrett.

Chip Bullen, an owner of Westport, maintains that residents don’t mind the trucks, and appreciate that the business is quiet on weekends when families are home.

“We’re open Monday through Friday, we’re closed on the weekends so our people can be with their family, and there’s no truck traffic,” he said.

But the terms of this exception do not comply with current county code regarding requirements for special exceptions to be granted in 2023, according to Chesapeake Legal Alliance (CLA) Staff Attorney Patrick DeArmey. CLA, Tutman, and community members worked together to address permit non-compliance and lack of zoning protections in the Lothian community. Using EPA’s Enforcement and Compliance History Online (ECHO) database, CLA found two closed solid waste landfill sites, five mobile home parks with wastewater treatment plants, and several sand and gravel mines with stormwater control permits. ECHO’s database allowed them to find many facilities out of compliance with their permits, according to the CLA’s DeArmey.

Tutman lives across the river from Lothian and called the Sands Road area a “sacrifice zone.” That term refers to populated areas – often low-income people of color – with high levels of pollution and environmental hazards. The constant noise, barrage of trucks, dust, and water pollution degrades day-to-day life for residents in Lothian.

Tutman observed and photographed each and every truck on Sand Roads one day, and saw sewage-only trucks, fertilizer-only trucks, and others heading into Westport. They are called a sand and gravel facility, so he wondered why fertilizer and sewage trucks were moving through their gates?

“We have no way to know what they’re dumping because there’s no transparency,” Tutman said. “This is a problematic special exception that needs to be fixed.”

Exposure to sewage sludge fertilizer causes people to suffer from respiratory issues, headaches, nausea, rashes, reproductive problems, cysts, and tumors, according to the Center for Food and Safety.

It is unlikely a facility of this sort would be permitted so close to a river without significant environmental controls under today’s laws, according to Tutman.

However, Bullen claims they only dump clean fill – soil, rock, brick, etc – and concrete up to a certain size. They stockpile this concrete and recycle and sell the material off site, although they do have a permit to dump it on-site.

“We’d rather keep it up and sell it. So you know, it’s basically creating a product out of this recycling,” said Bullen.

Tutman also observed that Westport doesn’t have any weight scales coming out of the facility, only going in.

“What kind of sand and gravel mine not only doesn’t have weight scales, but also doesn’t advertise sand and gravel on their website?” said Tutman.

Sands Road is zoned as Rural Agriculture which is “intended to preserve agricultural lands and provide for very low-density rural single-family detached residential development,” according to Anne Arundel County’s zoning classifications. Westport’s special exception exempts them as a sand and gravel mine from following Rural Agriculture zoning laws. With all the trucks moving through, Garrett says it’s more akin to a “diesel death cell.”

Brown lives on the other end of Sands Road in Harwood and she said 300 trucks per day drive through the narrow dirt road outside of her house. She worries about her own health, and that of her neighbors.

“You don’t know how long it takes before someone’s health has been degraded so much that you’re in a serious disease…the sound level was so loud, decibels of sound overtime can hurt hearing,” Brown said.

Garrett agrees. “Noise and air pollution affect your emotional, physical and spiritual health. All aspects of you holistically. There’s evidence of the impact of noise and air pollution on all aspects.”

The 56-year old special exception says “there shall be no harm to the public welfare from the standpoints of safety or devaluation of surrounding properties.” However, violations of public welfare do exist from Westport, including sedimented runoff from the site entering adjacent wetlands within the Chesapeake Bay Critical Area. This runoff was allowed because the stormwater permit does not have requirements preventing all runoff from leaving the property, according to Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE). In 2020 CLA shared drone footage of Westport’s proximity to the Critical Area with MDE, and they deemed it not a violation of any state laws, according to DeArmey.

The county inspector documented operation of a rock crusher, dumping, processing, resale of construction debris, a contractor’s yard, and storage of unregistered vehicles at Westport. Anne Arundel County Zoning Code prohibits the parking or storage of any vehicle that does not display all information required by law. So, the county filed a complaint, which led to a court hearing last summer, concluding in a consent agreement between Westport and the county. Westport agreed to pay a $3,000 penalty, cease contractor yard operations on the property, and remove junk vehicles. With their MDE permit the concrete crushing and biosoil blending are allowed as long as the special exception is in place.

After finding these numerous violations, CLA and a CLA volunteer attorney supported the complainants – Garrett and the Patuxent Riverkeeper – to challenge the Westport special exception before the Anne Arundel County Administrative Hearing Officer (AHO). The AHO initially sided with CLA’s clients and ordered Westport to cease operations immediately. However, Westport appealed this decision to the Anne Arundel Board of Appeals this past spring.

The appellate board denied the community members standing. In order to have standing – the legal right to initiate a lawsuit – in a hearing like this one, the complainants either have to be an adjacent landowner of the facility, or have a specialized reason for standing. CLA pro bono attorney Ryan Kennedy argued that Patuxent Riverkeeper and Garrett had standing because of their near lifelong proximity to the facility and the negative impact it had on their environment and wellbeing, but the appeals board did not agree.

Garrett was unable to demonstrate how she was affected differently than the public at large, because everyone on Sands Road experiences traffic, loud trucks, and fumes; she was not considered “specially aggrieved” according to the appeal decision. Since Garrett is not an “adjoining, confronting or nearby property owner” the appeals board found her unable to stand, even though she only lives half a mile from the Westport facility.

Then Kennedy tried to add additional people who live closer to Westport, but the appellate body denied them standing again.

“They were literally standing there in the room but they were not allowed to demonstrate why they would have legal standing to be heard,” said DeArmey.

The most recent decision from the appeals board in the Westport case says that no one can challenge the special exception unless they were part of the 1967 special exception renewal proceeding.

“It doesn’t make any sense at all. Particularly because it’s a special exception to do things that they’re not doing anymore. It’s not a special exception if they violate the terms of it. What they’re arguing is that nobody can review it to determine if they’re meeting the terms,” said Tutman.

Community members had 30 days to file an appeal, but that time-line passed this week. Moving forward, community members might hope for a different result and start the process over with people who live next to or across from the facility who have prima facie standing and are “specially aggrieved” and file a new petition before the Administrative Hearing Officer, according to DeArmey.

“We are evaluating all possible next steps…We aren’t going to let the decision from the Board of Appeals stop our efforts to protect the environment and better the quality of life of those who live on and around and use Sands Road. The county is not acting to protect its residents, so we have to keep trying,” DeArmey commented.

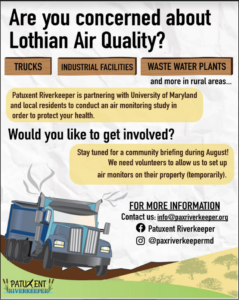

Community members have also been gathering to discuss strategies to combat the pollution they’ve been experiencing. Residents are currently working with the University of Maryland on getting air quality monitors in Lothian. Their next briefing is in late August.

“We’re going to do some good, “Garrett said. “We’re not just going to lay down.”