Looking Back on Trappe – A Conversation with the Choptank Riverkeeper

In January 2019, an application to operate a new wastewater treatment plant to serve the proposed Trappe Lakeside Development was submitted to Maryland regulators. The project was an effort 20 years in the making that had been resurrected, and as Matt Pluta, the Choptank Riverkeeper and Director of Riverkeeper Programs at ShoreRivers recalls, “What brought our attention to it, not only was it the sheer size of the development, which was proposed at 2,501 units, [which would make it] the largest development on the east coast of the country as the developers were quoted saying… but really the big thing was how is this new development going to treat their wastewater?”

The massive housing development had been sited to be built in the Choptank River watershed, a watershed listed by both the state of Maryland and the federal government as impaired by excessive nitrogen, phosphorus, sediment, bacteria, and other forms of pollution. Pluta states that this classification “effectively reduced…or eliminated the ability for the developer to create a new point source discharge through a new wastewater treatment plant, so it essentially put it on the developer and the town [who are] both applicants on all [the] permits to figure out, ‘alright, how are we going to treat this significant amount of waste which was proposed to be 540,000 gallons every day.” Another challenge facing the proposed development was that the existing wastewater treatment plant for the town of Trappe was known to be failing, causing downstream pollution in the stream.

“And so we knew just by face value that the plant could not accept the effluent from this new development based on the sheer volume of waste,” says Pluta. Additionally, the development would not be able to create a new point source and discharge directly into the river. So what solution did the development propose? A groundwater discharge permit. According to Pluta, the state often issues groundwater discharge permits for wastewater treatment plants that are proposing to either directly discharge into the groundwater, or in this case as the development proposed, to spray the wastewater as irrigation onto farm fields growing crops.

“In theory, it’s good,” says Pluta, “there’s beneficial reuse of any nutrients that are left in the effluent when being used. But in reality, what we know through decades of farming and land use management on the Eastern Shore is that agriculture is not a zero-sum game. There are most definitely nutrients that leak into the groundwater and that wash off overland during major rain events. And all of that ends up in our rivers eventually, but the state of Maryland seems to think that through their calculations, that one hundred percent of the nutrients that are applied to a farm field are taken up by the crops before it passes the root zone and we just don’t feel that is possible.”

According to a United States Geological Survey study more than half of the flow in the rivers on Maryland’s Eastern Shore come from groundwater. “So we have evidence there that our farmland is leaking nitrogen into the groundwater, which is ending up in our rivers,” states Pluta, adding that his organization’s concerns aren’t in regards to farming, but the adverse incentives that someone managing wastewater in an agricultural setting has over a farmer trying to grow a healthy crop for production purposes, because there is a different end goal. “In the wastewater side of things, your motivation is to apply as much wastewater as you can to the fields in the allowable time that you have in order to make room for quite literally the next flush that comes down the system; whereas as a farmer, you are only applying nutrients at the right time in the right way conducive to growing a healthy crop.”

It was shortly after this development plan was proposed that Pluta, who had already worked with CLA attorneys on previous matters, approached CLA on behalf of ShoreRivers. “I had worked with Evan [Isaacson] on previous permit renewal [challenges] for facilities in non-compliance, and I knew Evan was interested in addressing the loopholes presented through groundwater discharge permits, and the Trappe development presented almost the perfect opportunity to do that given the statewide focus that had been put on this development.”

Addressing the development’s groundwater discharge permit occurred in stages. When the first permit was issued by the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) in draft form, it had essentially authorized the full discharge amount through spray irrigation. In response, CLA and ShoreRivers highlighted a number of flaws and inconsistencies within the permit that related to how the agricultural sector and nutrient management plans are regulated. Specifically, the organizations targeted the nutrient application prohibition period, a period in Maryland stretching 3 months when it is illegal to apply nutrients to farm fields, and how MDE did not also prohibit wastewater management plants from applying effluent to farm fields during this period.

Additionally, CLA and ShoreRivers were concerned about transparency in the permitting process. “I’ll say the biggest thing that we petitioned for in that [initial] judicial review was that even though the state used the farmers’ nutrient management plans as a calculation for how zero nutrients were going to enter the groundwater, that nutrient plan was never made public,” says Pluta. “So because it was considered part of the treatment process, it essentially should have been part of the permit application, and because it was not a part of the application, the public did not have an opportunity to comment on it.”

Based on this theory, CLA Senior Attorney Evan Isaacson made the argument that the permit should be remanded because the nutrient management plan was not made public, depriving the public an opportunity to review it — and the state court agreed, remanding the permit back to the MDE, marking one early win in the legal battle.

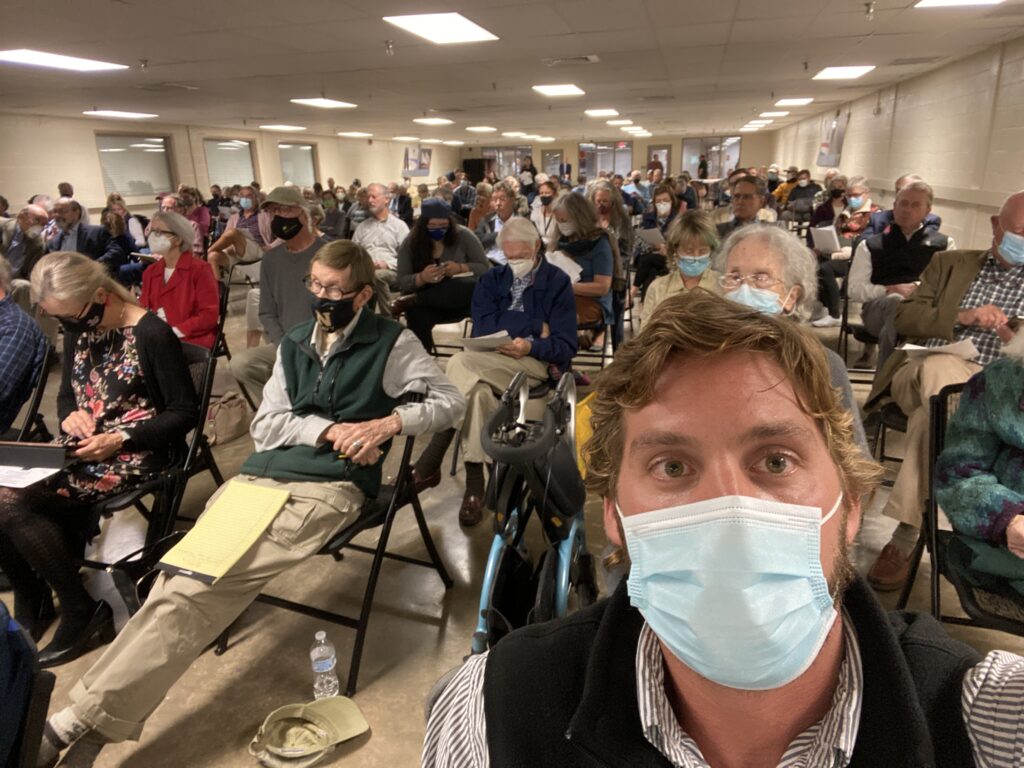

Once again, the judge sent the permit back to regulators, allowing for another public hearing and another opportunity for the public to add comments. With the help of some additional organizations, CLA and ShoreRivers were able to review the technical analysis of a consultant who pointed out that annual averages are not the most productive or protective way to go about authorizing groundwater discharge permits. The second comment period also enabled a hundred people to speak at the public hearing against the permit and thousands to send comments to Maryland regulators, which set a standard for future public participation at public hearings.

After helping the state understand how this permit would impact local waterbodies, the regulators issued the new permit. This time, they only allowed for 500 of the planned 2,500 homes to be built. This result was essentially an 86% reduction in the total volume of discharge originally planned. “That was a huge success,” says Pluta, “and getting the state to recognize that spraying all of this wastewater at the proposed amount was too problematic for water quality concerns, and that the best approach was to break the development into phases and reevaluate the initial impacts to groundwater was also important.”

Construction has since started on phase one of the development with a plan to hook up the first 120 homes to the existing Trappe wastewater treatment plant. Pluta believes this to be an ill-advised move because of the condition of the plant as well as the stream that the plant discharges into. Regardless, the developer is moving forward and has even applied for permits to develop phase two of the project, which is accompanied by new environmental concerns.

CLA and ShoreRivers will continue to analyze the development using MDE’s open data portal, a tool that CLA was instrumental in implementing, and has been a vital tool for ShoreRivers. “That’s what has allowed us to see, that through all of the construction with stormwater inspections and erosion control inspections, the developer is operating on a 25% non-compliance rate on some of those things, and that is sort of inexcusable in my opinion. And every time there is noncompliance, that means there is the potential for pollution going into our rivers, so we’re working right now on a strategy to bring back some control to the County level so that the County Council can have that similar influence in the approval process that the state has, just so we can have some accountability when any future phases are being applied for.”

“I really want to express my gratitude for Evan [Isaacson] and CLA taking on this case. I’ve been working with CLA since I started,” says Pluta. “I call you guys the army of lawyers, and just being able to work with Evan on this was a truly great experience. Without CLA’s help, I don’t think we would have ever been successful in the challenge on the first permit — and really just the whole knowledge base and the whole understanding of groundwater discharge permits and their ability to pollute our rivers and how they’re being used by Counties and local governments to sidestep TMDL regulations. That’s the big issue, so I’m looking forward to continuing to work with CLA on some potential legislative solutions to make sure that groundwater discharge permits in the state of Maryland are issued with an understanding of what their impact is on water quality.”